Drowned In Sound

80

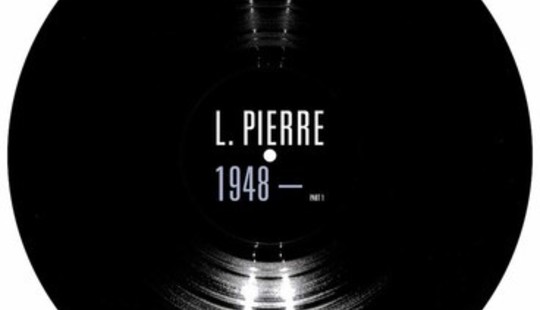

Y’know, I stared writing a conceit to match this conceit. A record to eulogize both Aidan Moffat’s L Pierre project and vinyl itself in one fell swoop? Well, why not also eulogize a fictional dead uncle who kept ten copies of the same naked record, and whose niece finds them each labeled by the year of their 'death'? Even now I’m savouring the final scene in my mind, where she sticks one on the turntable and lingers for an indeterminable time on the record’s final locked groove, lost in the all-consuming drone and the inescapable rumination of her own mortality… But nahhhhhhh. All that would just obscure the real dialogue that Moffat – self-depreciating front man of Arab Strap, prolific collage composer - wants us to engage in here. You can’t buy 1948 as a sleek digital package, or as a handy CD; nope, the only way to purchase L. Pierre’s last sample-strewn concerto is as a single record, with no sleeve or dust jacket whatsoever. 'I don’t want a pristine, digital document that could last forever,' Moffat told Melodic in a letter. 'I want the music left to the elements; I want it to live and scar.' This isn’t a question of which medium trumps the other; rather, 1948 challenges the record-buying public head-on with its inherent weakness.

Reviewing such a record, then, becomes quite the task for yours truly. Because a), as an American critic, I must assess a digital copy, because post is slow and time is of the essence. And b), Moffat stitched this together with very large swaths from the first 12-inch ever pressed, a copy of Nathan Milstein’s version of a Mendelssohn concerto (hence, 1948) – which means, it’s so hella second-hand, that the casual listener would struggle to discern between Milstein’s own technical prowess, and L.Pierre’s plucky engineering.

Now, I’m not the casual listener, but I’d rather grapple the conceit. 1948 strikes directly at the 'resurgence' of an obsolete format, the record, in the digital era. I write that in scare quotes, because while millennials snapped up plenty of fancy splatter discs and Africa-shaped singles last weekend, they likely won’t ever slip that swag under the needle. According to a study from the BBC last year, nearly half of the folk who bought records that week hadn’t actually played them; some didn’t even own a turntable. And you’ve heard from us before of the LP’s “token” value in the modern market, how the young’uns crave trophies to substantiate their digital libraries and bolster their social profile. Those selfish impulses not only reduce music to transactions, but also music fans to mere consumers – and preservation of the product maintains that status quo. Who wants to show off a hot pink LP with a few barely perceptible scratch marks?

Me, I’m reminded of the one lesson from Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 that’s stuck with me for over a decade. Around the midpoint of the novel, the protagonist, a professional book burner, learns from a professor-type that vessels of art are inherently worthless – it’s the content, not the package, that merits protection. Granted, the art contained within records is more fluid than that stored in books: a charred page can’t be read, but a scratched record yields a new quirk in the recording. So 1948 proposes more than an ousting of the record’s immortality – it offers the listener a chance to rewrite an old work of art into something new.

So, from a purely conceptual level, I can get behind L. Pierre here. I’m all for encouraging hands-on engagement with art instead of complacent wall-hanging and artful shelving. Regarding the content itself, though – well, the source material is nice, but only a few alterations stand out. In the fourth movement, especially, reversed echoes and static jolts remind the listener of their place in a palimpsest, with the past eroding ever so slowly underneath like a cliff in the desert. And the ending, that aforementioned locked groove, cinches the whole conceit: just an abyssal drone, stretching on and on until the listener lifts the needle.

All told, the lovely but tedious collage work of 1948 isn’t crucial to hear. But the blank death date on its inner label deserves an answer: if we continue to covet records as tokens, instead of malleable containers, should they persist?

Wed Apr 26 13:53:28 GMT 2017