Drowned In Sound

80

'I got a text from my agent saying, "Greta Gerwig just directed her first movie, are you interested in seeing it?" I said yes! I saw it, I liked it. We talked on the phone and then we spent a day working and liked each other. I’d love to tell you some colourful circuitous story but it’s not there.' Those were Jon Brion’s words to Crack Magazine earlier this month, but the truth of the matter is that Gerwig didn’t sound out Brion by accident. She might have liked his production work, particularly with Fiona Apple on When the Pawn... It could’ve have been a case of superficial admiration of his scores for the likes of Magnolia, Punch-Drunk Love and I Heart Huckabees. But, likelier than not, Gerwig realised that there are few, if any, soundtrackers in Hollywood who understand how efficiently a less-is-more approach can lend considerable emotional heft to a picture precisely like Brion does.

His masterpiece is his work on Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, a film in which his music quietly did so much of the heavy lifting; given the mind-bending inventiveness of the script, the towering, chalk-and-cheese lead performances from Jim Carrey and Kate Winslet and the deft execution of the central science fiction concept, that is no small achievement on Brion’s part. He understood the focus on memory in terms of both feeling and intellect, creating a handful of yearning motifs and then making subtle instrumental changes to them to suit the scene as the film wore on; scratchy, washed-out guitar early on to represent the initial queasiness of Carrey’s character, and then pretty acoustic later over the sweeter flashbacks. In places, distortion and backmasking crept in as an aural accompaniment to the sight of the past literally collapsing around the main characters.

It required ingenuity of both the head and the heart on Brion’s part and apparently moved Kanye West sufficiently to compel him to bring in the producer – previously unversed in the world of hip hop – to helm Late Registration in 2005. Gerwig’s Lady Bird isn’t such an outwardly cerebral affair but for all its low-budget charm, it will not have proved a straightforward assignment for Brion. He may well have been able to empathise through experience with Eternal Sunshine’s lovelorn leads; getting inside the mind of a 17-year-old girl furious at small-town limitations, you imagine, would’ve been another matter entirely.

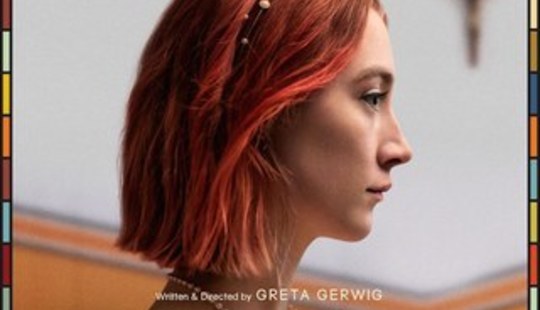

Lady Bird has variously been described as a teen movie and a coming-of-age tale but as its unanimously positive critical reception and heap of awards nominations have already demonstrated, it's much more than the sum of those two relatively minor parts. It is, though, a pleasantly bittersweet story about the no-person's-land between adolescence and adulthood and, accordingly, was always going to require a gentle touch from Brion, relatively unchartered territory for somebody who's past film work has run the gamut from Eternal Sunshine's eclipsed romance to Synecdoche, New York's stare-into-the-void nihilism.

The film’s relationship with popular music is a peculiar one, too. Much has already been made about the fact that ‘Crash Into Me’, by the Dave Matthews Band, plays an important narrative role in the film. It does feel like one of those cinematic moments that forces you to reassess your own relationship with a certain track, in the same vein as Steve Coogan and Rob Brydon blasting out Jagged Little Pill across Italy during the second series of The Trip (incidentally, ‘Hand in My Pocket’ appears in Lady Bird, only to be blithely cut down by Tracy Letts’ quietly cynical dad as part of an early gag).

All of that means that Gerwig’s own contribution towards the music of the film shouldn’t be ignored, especially given that she clearly made a conscious decision to plaster the walls of Lady Bird’s bedroom with posters from the likes of Bikini Kill and Sleater-Kinney, but never actually called upon those bands, both of whom - for their own reasons - would’ve been fashionable in the 2002 that the movie presents. Instead, it’s left to Brion’s score to underline Lady Bird’s myriad minor rebellions, from her dramatic jump from her mother’s car in the opening scene to her eschewing of her own family’s Thanksgiving to try her hand at class-climbing to the movie’s throughline - her quiet, unshakeable determination to leave Sacramento for an east coast college.

There’s no swinging drama in Brion’s work on Lady Bird, but the meaning isn’t hard to find, either; it’s light, but not frothy. Above all, just like the film, it’s warm as toast; shuffling, almost Spanish acoustic guitars soundtrack Lady Bird’s first kiss, and subtly mischievous minor key brass swells provide the backdrop to her and her mother indulging in one of their favourite pastimes; noseying around open houses at properties they could never hope to buy.

Brion’s score is from the measured perspective of an observer - you have to think that if Lady Bird herself could’ve provided the music, there’d be far more melodrama involved - and there’s an unassuming wisdom to it that might only properly reveal itself with repeat viewings of the film. Brion might never have been a teenage girl, but he will have been an angsty, ambitious teenager, and he’ll have looked back at that time, over subsequent decades, wishing he could tell that version of himself that this too will pass. His soundtrack – just like Gerwig’s film – is a love letter to that period.

Fri Feb 23 17:04:28 GMT 2018